MTA Turnstile Data Analysis

Our first project at Metis was essentially an exercise in exploratory data analysis. Our assignment was to help a fictional client WomenTechWomenYes (WTWY) decide at which subway stations to place canvassers, with the trifold goal of increasing attendance for their summer gala, general awareness, and fundraising. To that end, we not only focused on the number of people reached, but the kinds of people and whether they might be interested in WTWY.

This was a good first project to introduce us to the world of data science because the MTA turnstile data that we were supposed to use required a lot of cleaning.

My group’s final proposal rested on a few assumptions:

- We would look at data for the month of May only, because the event would be in the early summer

- We would focus only on exit data (rather than entries), because we figured people getting out of the subway might be more likely to stop, and the people would have a higher likelihood of passing by the station again if they stayed in the area

- We would eliminate “non-regular” turnstile readings

The last point is where the serious cleaning came in.

After reading in our data with pandas ![]() and trying a few things, we found the following issues:

and trying a few things, we found the following issues:

- There can be multiple “remote units” per station (still not totally what those are, but probably a group of turnstiles)

- There are multiple stations with the same exact name (like 28th St, which is on both the 456 line and 123 line)

- The turnstile counters represent cumulative entries or exits and not absolute numbers

- The counters usually count up, eventually hit some number, and reset to 0, but sometimes they count down

- The readings are generally 4 hours apart, but they range from minutes apart to 20+ hours apart, and can be taken at any time of day

- Some of the readings are duplicates

To account for these issues we grouped stations by a combination of their name and lines, we took the absolute value of the difference in the counters from one time to the next time, we eliminated any time that showed over 5,000 people entering or exiting (assuming that anything larger would represent a reset of the counter), we eliminated readings taken more than 4 hours apart, and we eliminated non “REGULAR” types to deal with duplicates.

Here is a snapshot of our dataframe at this point, sorted by highest exits:

| C/A | UNIT | SCP | STATION | LINENAME | DIVISION | DATE | TIME | DESC | ENTRIES | EXITS | DATE_TIME | TIMEDIFF | HRSDIFF | DAY_OF_WK | DAY_OF_WK_N | LINESORT | STAT_MERGE | DELTA_ENTRIES | DELTA_EXITS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49024 | N063A | R011 | 00-00-00 | 42 ST-PORT AUTH | ACENQRS1237W | IND | 2017-05-22 | 20:00:00 | REGULAR | 16459422 | 57736969 | 2017-05-22 20:00:00 | 04:00:00 | 4 | Monday | 0 | 1237ACENQRSW | 42 ST-PORT AUTH-1237ACENQRSW | 68.0 | 4888.0 |

| 153200 | R238 | R046 | 00-03-00 | GRD CNTRL-42 ST | 4567S | IRT | 2017-04-26 | 12:00:00 | REGULAR | 13464905 | 4960372 | 2017-04-26 12:00:00 | 04:00:00 | 4 | Wednesday | 2 | 4567S | GRD CNTRL-42 ST-4567S | 677.0 | 4876.0 |

| 153206 | R238 | R046 | 00-03-00 | GRD CNTRL-42 ST | 4567S | IRT | 2017-04-27 | 12:00:00 | REGULAR | 13469687 | 4973876 | 2017-04-27 12:00:00 | 04:00:00 | 4 | Thursday | 3 | 4567S | GRD CNTRL-42 ST-4567S | 705.0 | 4870.0 |

| 153194 | R238 | R046 | 00-03-00 | GRD CNTRL-42 ST | 4567S | IRT | 2017-04-25 | 12:00:00 | REGULAR | 13462328 | 4945957 | 2017-04-25 12:00:00 | 04:00:00 | 4 | Tuesday | 1 | 4567S | GRD CNTRL-42 ST-4567S | 656.0 | 4868.0 |

| 153250 | R238 | R046 | 00-03-01 | GRD CNTRL-42 ST | 4567S | IRT | 2017-04-27 | 20:00:00 | REGULAR | 17952071 | 7090305 | 2017-04-27 20:00:00 | 04:00:00 | 4 | Thursday | 3 | 4567S | GRD CNTRL-42 ST-4567S | 0.0 | 4850.0 |

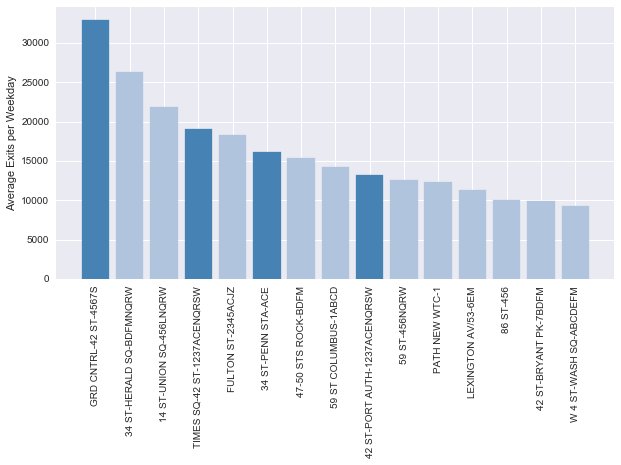

Here are the top stations by average number of exits per weekday:

We then wanted to look at the data eliminating these dark blue stations, which represent the big commuter and tourist hubs in the city. The thought was that the people coming through these stations are probably not from the city, and might not be interested in the event, and these stations are too full of crazy stressed commuters during rush hour who won’t want to stop for anything.

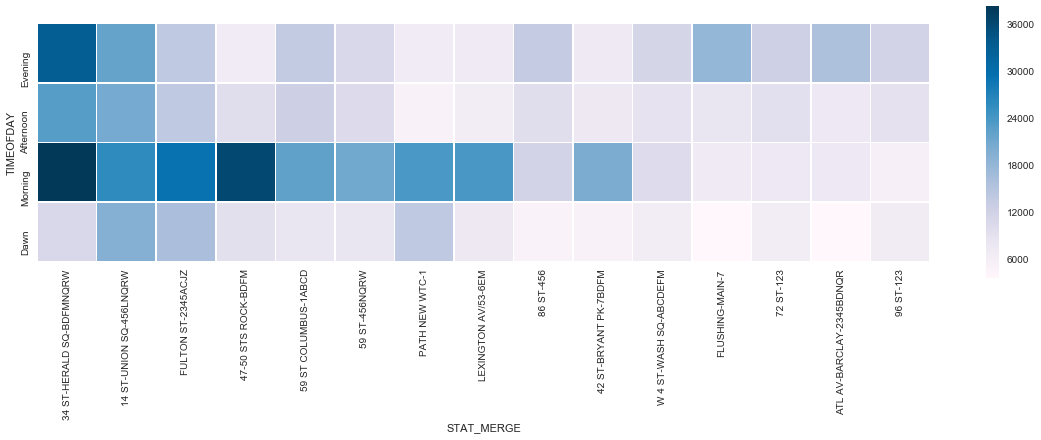

Eliminating these stations, we produced a heatmap of the remaining top 15 stations by time of day (only for weekdays) to get an idea of where and when the bulk of the traffic occurred.

This addresses our quantity of people question, but not our quality of people question. To solve this, we looked at income data from the IRS broken down by zipcode (wealthier people are more likely to donate) and data on tech company addresses in NYC (people in tech are more likely to be intereted in WTWY and attend the event). We assumed that people exiting the subway in the morning were probably going to work, so in the morning we would focus on the tech company data, and in the evening people were going home, so in the evening we would focus on the income data.

The tech company data showed that tech hubs in the city were located nearest Fulton Street station, Union Square, Herald Square, and Bryant Park.

The income data showed that the wealthiest neighborhoods in NYC were the Upper East and West Sides, Chelsea, the Gramercy/Murray Hill area, so in the evenings we recommended hitting Union Square, Columbus Circle, 86th Street (on the 456), 72nd Street (on the 123), and West 4th Street in the Village.

Being a New Yorker ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , I grappled a little bit with how much of our insights were supposed to come from the data, and how much we could allow to be informed by our prior knowledge. For example, Flushing came up as a top station, but I instinctively knew it wouldn’t be a good candidate for canvassing. It then became a matter of finding data that would eliminate that station. I wonder how I would’ve solved the problem having known nothing about New York. Cleaning the data also would have been a lot harder without already knowing the nuances of the subway system. So my biggest question going forward is if you are more likely to find a new or interesting insight if you have broad domain knowledge and certain expectations, or if you come into something with neutral eyes. Nonetheless, it was amazing to see what we could come up with only 4 days into being data scientists!

, I grappled a little bit with how much of our insights were supposed to come from the data, and how much we could allow to be informed by our prior knowledge. For example, Flushing came up as a top station, but I instinctively knew it wouldn’t be a good candidate for canvassing. It then became a matter of finding data that would eliminate that station. I wonder how I would’ve solved the problem having known nothing about New York. Cleaning the data also would have been a lot harder without already knowing the nuances of the subway system. So my biggest question going forward is if you are more likely to find a new or interesting insight if you have broad domain knowledge and certain expectations, or if you come into something with neutral eyes. Nonetheless, it was amazing to see what we could come up with only 4 days into being data scientists!